Lill-Tycho i bild

Så utomordentligt roligt!

♡ När vännerna inom Malmö Förskönings- och Planteringsförening besökte oss på Tycho Brahe-observatoriet härom kvällen, var också föreningens sekreterare Sally Petersen på plats. Hon påpekade att barnbarnet faktiskt fått Tycho som mellannamn när han döptes, och här är det festliga bildbeviset när Finn Tycho var tre månader gammal:

♡ Vad månde bliva?

♡ Personligen gillar jag den nya versionen av Elefantorden.

♡ Sally berättar:

– Lill-Tycho bor i Håslöv och blir 1 år den 15 december. Jag är hans mormor och föräldrarna heter Moa Goysdotter – min man heter Goy – och Kristian Petersen.

– I familjen finns också Rikke, 4 år.

♡ Grattis i förhand till Lill-Tycho på ettårsdagen! – det får bli med lite virtuella godisnappar!

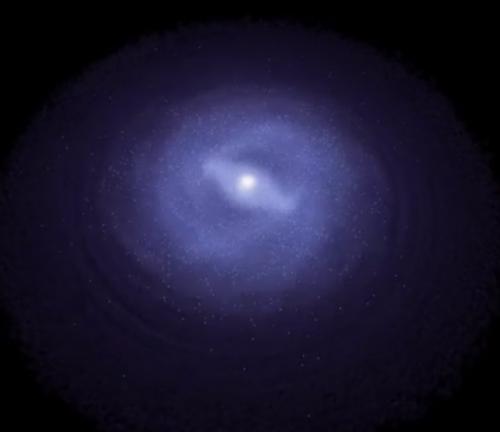

If you took a photograph of the Milky Way galaxy today from a distance, the photo would show a spiral galaxy with a bright, central bar (sometimes called a bulge) of dense star populations. The Sun—very difficult to see in your photo—would be located outside this bar near one of the spiral arms composed of stars and interstellar dust. Beyond the visible galaxy would be a dark matter halo—invisible to your camera but important nonetheless because it keeps everything together by dragging down the rotational velocity of the bar and spiral arms.

Now, if you wanted to go back in time and take a video of the Milky Way forming, you could go back 10 billion years, but many of the galaxy's prominent features would not be recognizable. You would have to wait about 5 billion years to witness the formation of the Earth's solar system. By this point, 4.6 billion years ago, the galaxy looks almost like it does today.

"The grand structure of the galaxy has emerged from the self-organization of the stellar distribution over the past 10 billion years to eventually look like the Milky Way in the photo," said Simon Portegies Zwart of Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands.

This is the timeline a team of researchers from the Netherlands and Japan, including Portegies Zwart, are seeing emerge when they use supercomputers to simulate the Milky Way galaxy's evolution. Using a code developed for GPU supercomputing architectures—including that of the Cray XK7 Titan located at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory—the team's simulations have earned acceptance as a Gordon Bell Prize finalist. The prize recognizes outstanding achievement in high-performance computing and will be presented by the Association for Computing Machinery at SC14 on November 20.

"We don't really know how the structure of the galaxy came about," Portegies Zwart said. "What we realized is we can use the positions, velocities, and masses of stars in three-dimensional space to allow the structure to emerge out of the self-gravity of the system."

The challenge of computing galactic structure on a star-by-star basis is, as you might imagine, the sheer number of stars in the Milky Way—at least 100 billion. Therefore, the team needed at least a 100 billion-particle simulation to connect all the dots. Before the development of the team's code, known as Bonsai, the largest galaxy simulation topped out around 100 million—not billion—particles.

The team tested an early version of Bonsai on the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility's Titan, the second-most-powerful supercomputer in the world, to improve scalability in the code. After scaling Bonsai to almost half of Titan's GPU nodes, the team ran Bonsai on the Piz Daint supercomputer at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre and simulated galaxy formation over 6 billion years with 51 million particles representing the forces of stars and dark matter. After a successful Piz Daint run, the team returned to Titan to maximize the code's parallelism.

The Bonsai code demonstrated scalability on 18,600 Titan nodes (96% of the machine's GPU nodes), which would enable an 8 million-year, 242 billion-particle Milky Way simulation. Bonsai achieved nearly 25 petaflops of sustained single-precision, floating point performance on Titan. Single-precision floating-point operations use less memory by representing numbers using 32 bits, whereas double-precision operations represent more precise numbers at the expense of using 64 bits.

"With graduate student Jeroen Bédorf, we started by writing single code for GPUs and deliberately never wrote code on CPUs because we wanted the entire code to run on GPUs to exploit their parallelism," Portegies Zwart said. "The host CPUs are only used to streamline the communication between the nodes and the GPUs. In this way, we can fully optimize the use of GPUs for number crunching and the much slower CPUs to minimize the communication overhead."

Another feature of Bonsai that makes 242 billion-particle simulations feasible is the use of a hierarchal tree-code that eliminates direct gravitational force calculations between each particle (or star) and all the other billions of particles by organizing them into octants that prioritize particle interactions.

The team aims to compare simulation results to new observations coming from the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite that launched last year. The Gaia mission is currently cataloguing star measurements—including distances, velocities, and stellar type—of one billion Milky Way stars.

"One percent of the particles, or stars, in our simulated galaxy should match Gaia data," Portegies Zwart said.

Gaia will also provide data on stars farther than Earth's Solar Neighborhood, or only stars within tens of light-years. When compared with Bonsai simulations, these new observations will help researchers better understand larger galaxy dynamics, such as the interaction of the bar and spiral arms, in addition to local dynamics taking place around the Solar Neighborhood.

Because the galaxy is a big place with many research teams dedicated to understanding it, Portegies Zwart's team plans to make simulation data and source code resulting from Bonsai projects available to the research community.

Explore further: How small can galaxies be?

Explore further: How small can galaxies be?

Mer om Tycho

I dag (fredag 28.11) började vi klä på Tycho Brahe-dockan ute på TB-observatoriet, Oxie. På plats var dräktens skapare Christina "Tina" Åberg och smakrådet, astronomiintresserade skådisen och regissören Arne Strömgren.

❀ Dräkten bars av Christinas bortgångne bror, skådespelaren Christer Söderlund, som bodde på Ven med hustrun Anita Agerlo och som var en stor Ven-profil – och Tycho Brahe-kännare.

Christina finputsar Tycho! Foto: Peter Hemborg

♡ Tycho kläs på:

Trion Ulf R, Peter Hemborg och Tina i aktion. Foto: Arne Strömgren

❀ Rapport – med fler bildbevis – följer på vår TBOBS-sajt!

Ännu mer om Tycho

Det är den astronomiske stigfinnaren Christian Vestergaard, som hittat detta imponerande diktverk om astronomins historiska giganter inkusive Tycho Brahe:

Watchers of the Sky, av Alfred Noyes.

Pyssel

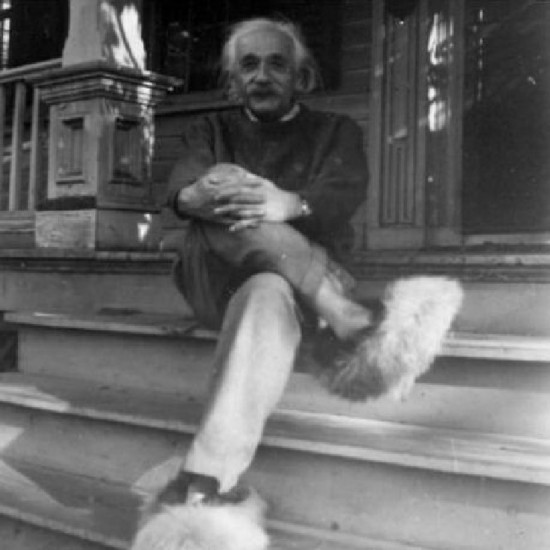

Vems morgontofflor är detta?

Rätt svar längst ner i denna utgåva av W-bloggen.

If you took a photograph of the Milky Way galaxy today from a distance, the photo would show a spiral galaxy with a bright, central bar (sometimes called a bulge) of dense star populations. The Sun—very difficult to see in your photo—would be located outside this bar near one of the spiral arms composed of stars and interstellar dust. Beyond the visible galaxy would be a dark matter halo—invisible to your camera but important nonetheless because it keeps everything together by dragging down the rotational velocity of the bar and spiral arms.

Now, if you wanted to go back in time and take a video of the Milky Way forming, you could go back 10 billion years, but many of the galaxy's prominent features would not be recognizable. You would have to wait about 5 billion years to witness the formation of the Earth's solar system. By this point, 4.6 billion years ago, the galaxy looks almost like it does today.

"The grand structure of the galaxy has emerged from the self-organization of the stellar distribution over the past 10 billion years to eventually look like the Milky Way in the photo," said Simon Portegies Zwart of Leiden Observatory in the Netherlands.

This is the timeline a team of researchers from the Netherlands and Japan, including Portegies Zwart, are seeing emerge when they use supercomputers to simulate the Milky Way galaxy's evolution. Using a code developed for GPU supercomputing architectures—including that of the Cray XK7 Titan located at the Department of Energy's Oak Ridge National Laboratory—the team's simulations have earned acceptance as a Gordon Bell Prize finalist. The prize recognizes outstanding achievement in high-performance computing and will be presented by the Association for Computing Machinery at SC14 on November 20.

"We don't really know how the structure of the galaxy came about," Portegies Zwart said. "What we realized is we can use the positions, velocities, and masses of stars in three-dimensional space to allow the structure to emerge out of the self-gravity of the system."

The challenge of computing galactic structure on a star-by-star basis is, as you might imagine, the sheer number of stars in the Milky Way—at least 100 billion. Therefore, the team needed at least a 100 billion-particle simulation to connect all the dots. Before the development of the team's code, known as Bonsai, the largest galaxy simulation topped out around 100 million—not billion—particles.

The team tested an early version of Bonsai on the Oak Ridge Leadership Computing Facility's Titan, the second-most-powerful supercomputer in the world, to improve scalability in the code. After scaling Bonsai to almost half of Titan's GPU nodes, the team ran Bonsai on the Piz Daint supercomputer at the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre and simulated galaxy formation over 6 billion years with 51 million particles representing the forces of stars and dark matter. After a successful Piz Daint run, the team returned to Titan to maximize the code's parallelism.

The Bonsai code demonstrated scalability on 18,600 Titan nodes (96% of the machine's GPU nodes), which would enable an 8 million-year, 242 billion-particle Milky Way simulation. Bonsai achieved nearly 25 petaflops of sustained single-precision, floating point performance on Titan. Single-precision floating-point operations use less memory by representing numbers using 32 bits, whereas double-precision operations represent more precise numbers at the expense of using 64 bits.

"With graduate student Jeroen Bédorf, we started by writing single code for GPUs and deliberately never wrote code on CPUs because we wanted the entire code to run on GPUs to exploit their parallelism," Portegies Zwart said. "The host CPUs are only used to streamline the communication between the nodes and the GPUs. In this way, we can fully optimize the use of GPUs for number crunching and the much slower CPUs to minimize the communication overhead."

Another feature of Bonsai that makes 242 billion-particle simulations feasible is the use of a hierarchal tree-code that eliminates direct gravitational force calculations between each particle (or star) and all the other billions of particles by organizing them into octants that prioritize particle interactions.

The team aims to compare simulation results to new observations coming from the European Space Agency's Gaia satellite that launched last year. The Gaia mission is currently cataloguing star measurements—including distances, velocities, and stellar type—of one billion Milky Way stars.

"One percent of the particles, or stars, in our simulated galaxy should match Gaia data," Portegies Zwart said.

Gaia will also provide data on stars farther than Earth's Solar Neighborhood, or only stars within tens of light-years. When compared with Bonsai simulations, these new observations will help researchers better understand larger galaxy dynamics, such as the interaction of the bar and spiral arms, in addition to local dynamics taking place around the Solar Neighborhood.

Because the galaxy is a big place with many research teams dedicated to understanding it, Portegies Zwart's team plans to make simulation data and source code resulting from Bonsai projects available to the research community.

Explore further: How small can galaxies be?

Explore further: How small can galaxies be?

Tegmark föreläser

Vår ASTB:are Kjell Werner har luskat ut att Max Tegmark, MIT-professor och författare till bestsellern Vårt matematiska universum, ska hålla en tvåtimmarsföreläsning 14 januari 2015. Plats: Medborgarskolan, Stockholm.

Populär föreläsare. Snart på ett obsis nära dig…?

Kjell W kollar just nu möjligheterna för direktsändning ner till oss men har ju också lovat presentera boken (som kommer att finnas till utlån på vårt nya TBO-bibliotek) på kommande stormöte 4 december.

MFF:s stjärnsmäll

Fotbollsexpertisen hävdar att det var domarens mörka energi som fällde MFF i Juventus-mötet härom kvällen, men det jag såg pekade på klasskillnad. Peter Hemborg fastnade för denna astropedagogiska fotbollsrubrik i Sur… Sydsvenskan:

Makalös Vintergats-simulering

Den senaste, helt otroliga datorsimuleringen av Vintergatans 100 miljarder stjärnor under deras rörelser under ett antal miljarder år har gjorts vid Oak Ridge National Laboratory i USA. Några av världens absolut häftigaste superdatorer har använts, och förhoppningen är att materialet ska kunna jämföras med Gaia:s astrometriska skattningar i tre dimensioner.

Bildkälla: ORNL

På sajten ovan finns en Youtube-hänvisning, som rekommenderas.

Morgontoffel-gåtan löst!

Tack till Lars Olefeldt, som satte oss på det hala. Det är naturligtvis Albert Einstein som kopplar av i morgontofflor. Var nånstans bilden är tagen och när – proveniensen – är för W-bloggen okänt.

Bildkälla: Nätet under sökorden "Albert Einstein in slippers"